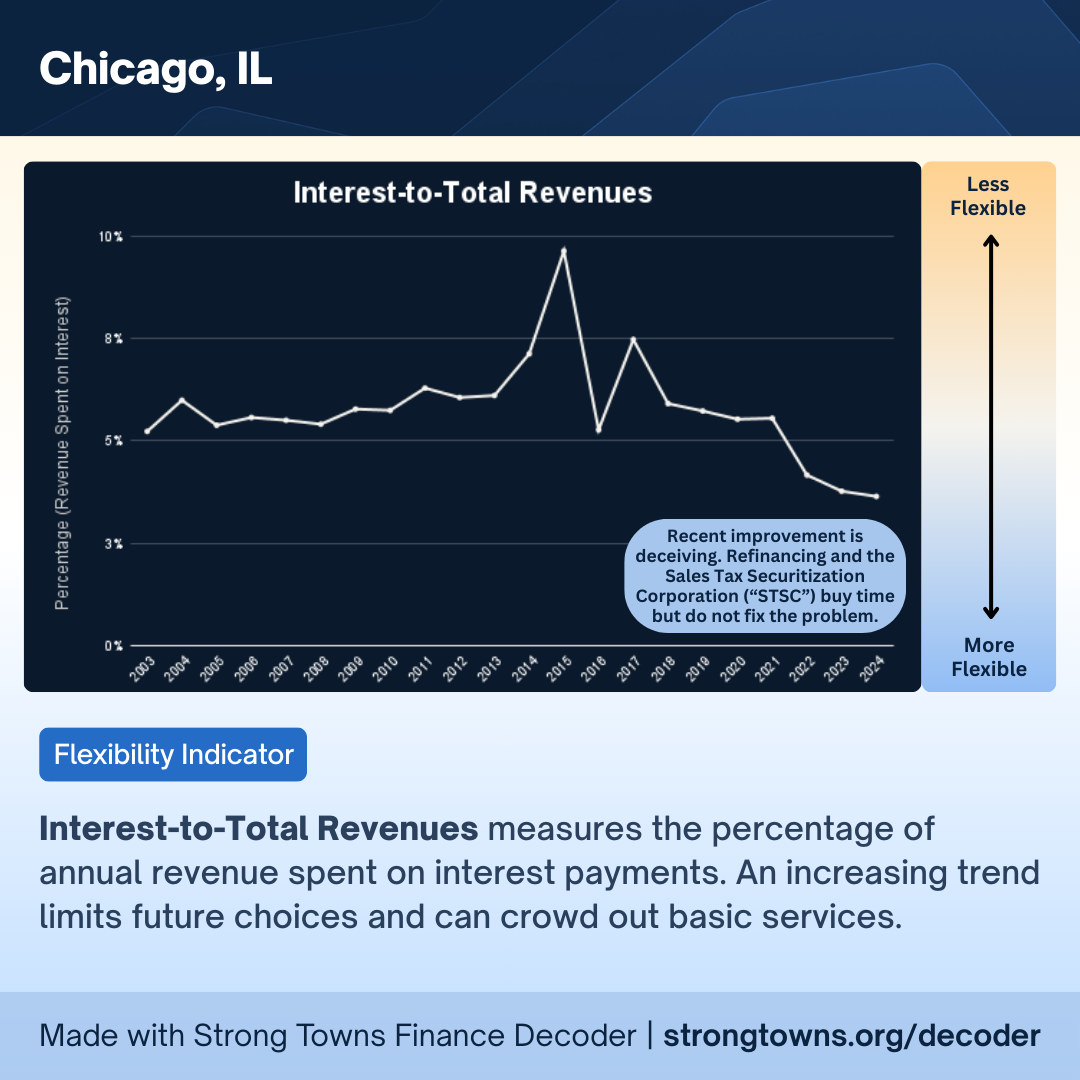

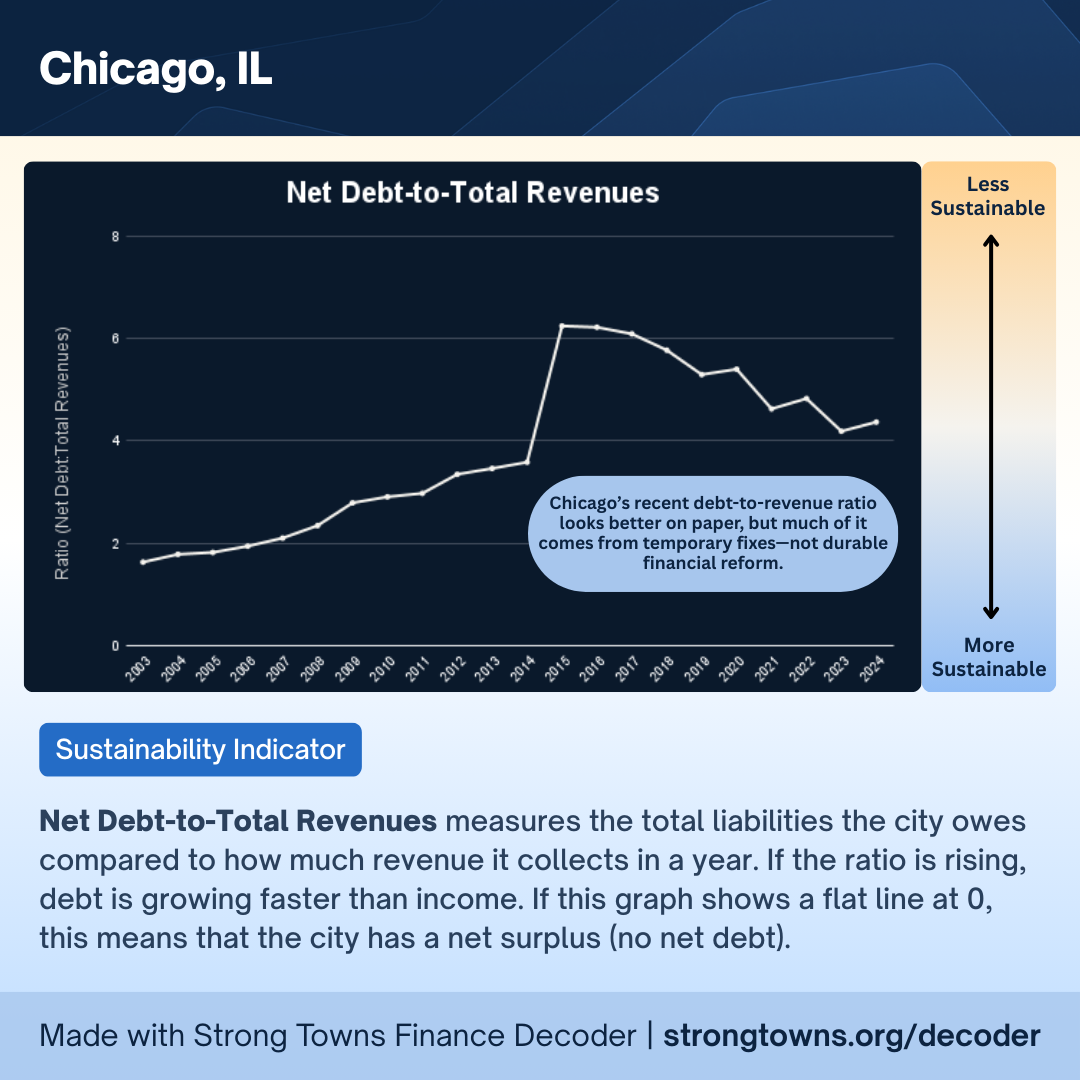

A core Strong Towns principle is that financial solvency is a prerequisite for long-term prosperity. As seen in the below charts, Chicago is operating right at the edge because for too long, we’ve made big decisions while treating long-term community finances as an afterthought.

Improved fiscal responsibility and transparent local accounting would allow Chicago to reliably invest in transit, housing, and parks—supporting safer streets, better services, and a higher quality of life without constant crises, tradeoffs, and tax hikes.

The Finance Decoder powers Strong Towns Chicago’s #DoTheMath initiative, a finance-first playbook for smarter local decisions. We charted 20+ years of data and challenge our local leaders to study it, then ask three plain questions of every budget, project, and policy:

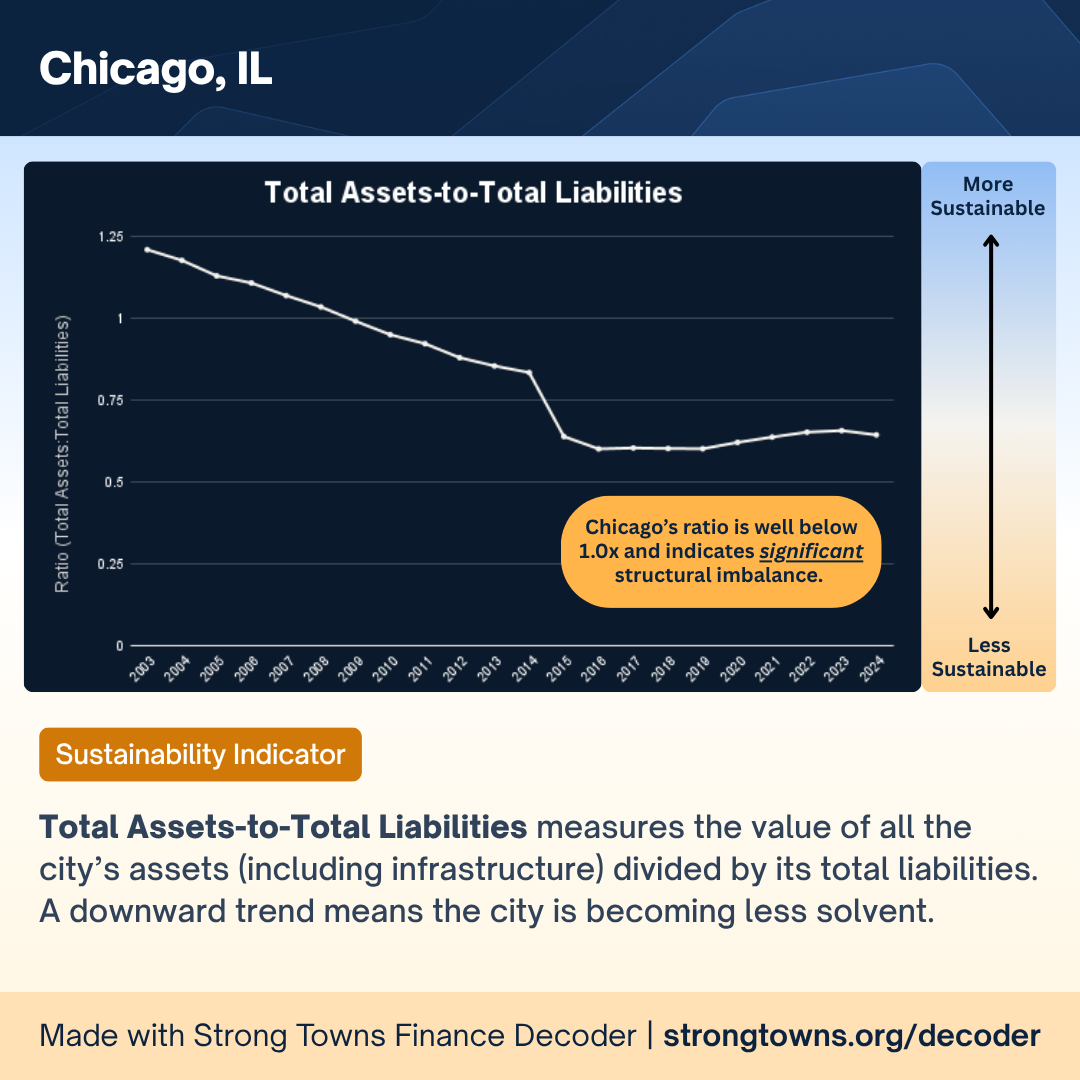

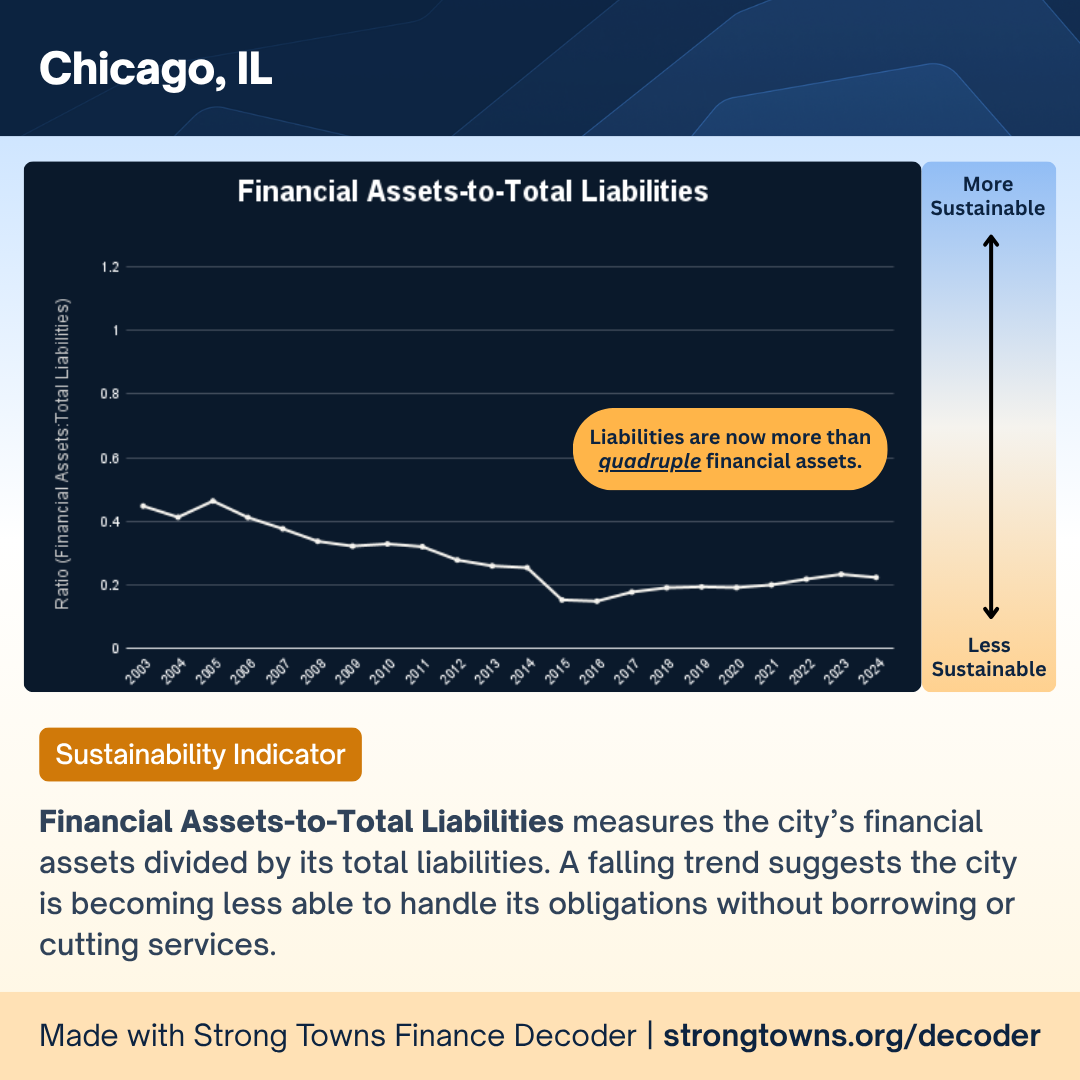

Sustainability: “Can Chicago sustain today’s service levels over the long term?”

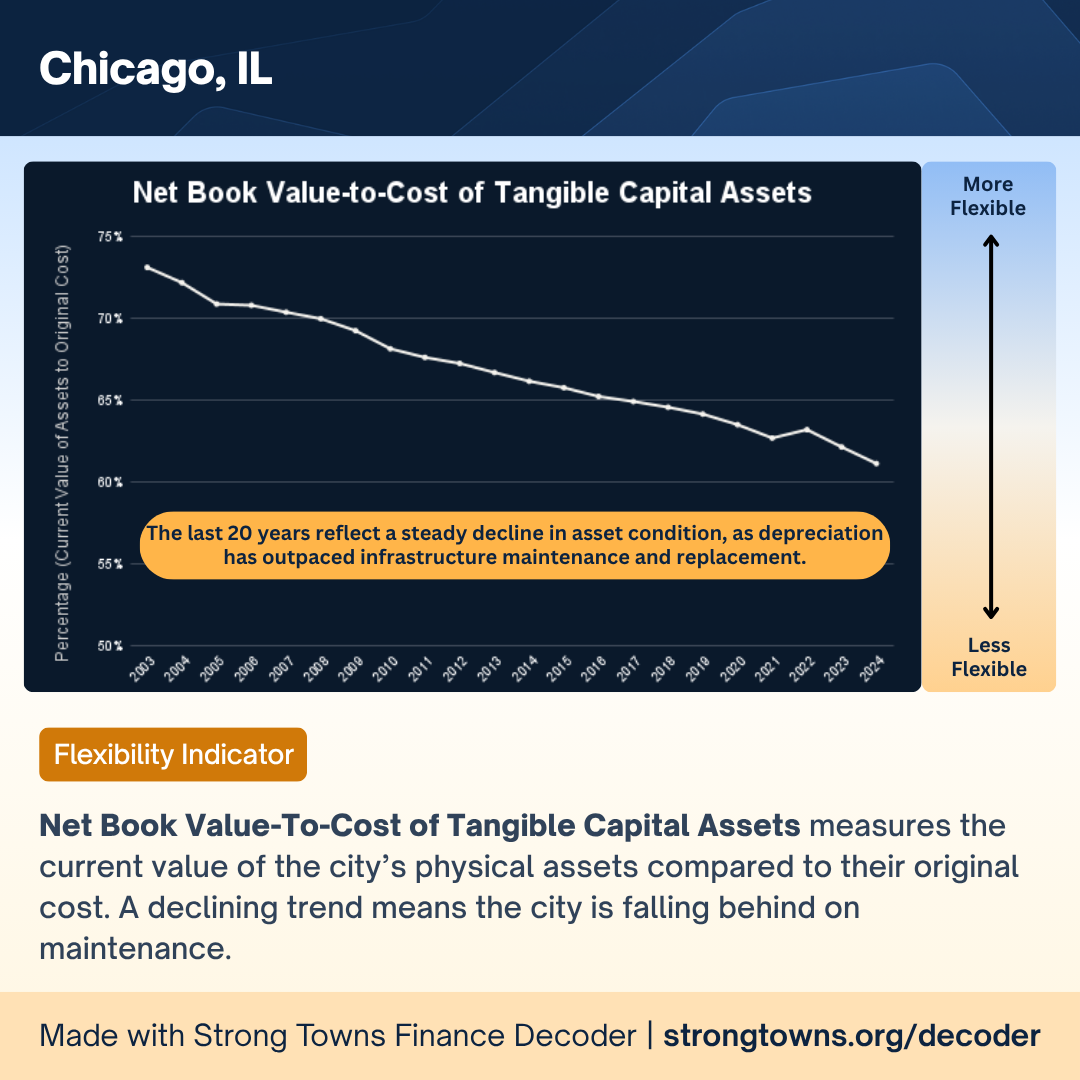

Flexibility: “How much budgetary slack does Chicago have to adapt to unexpected change?”

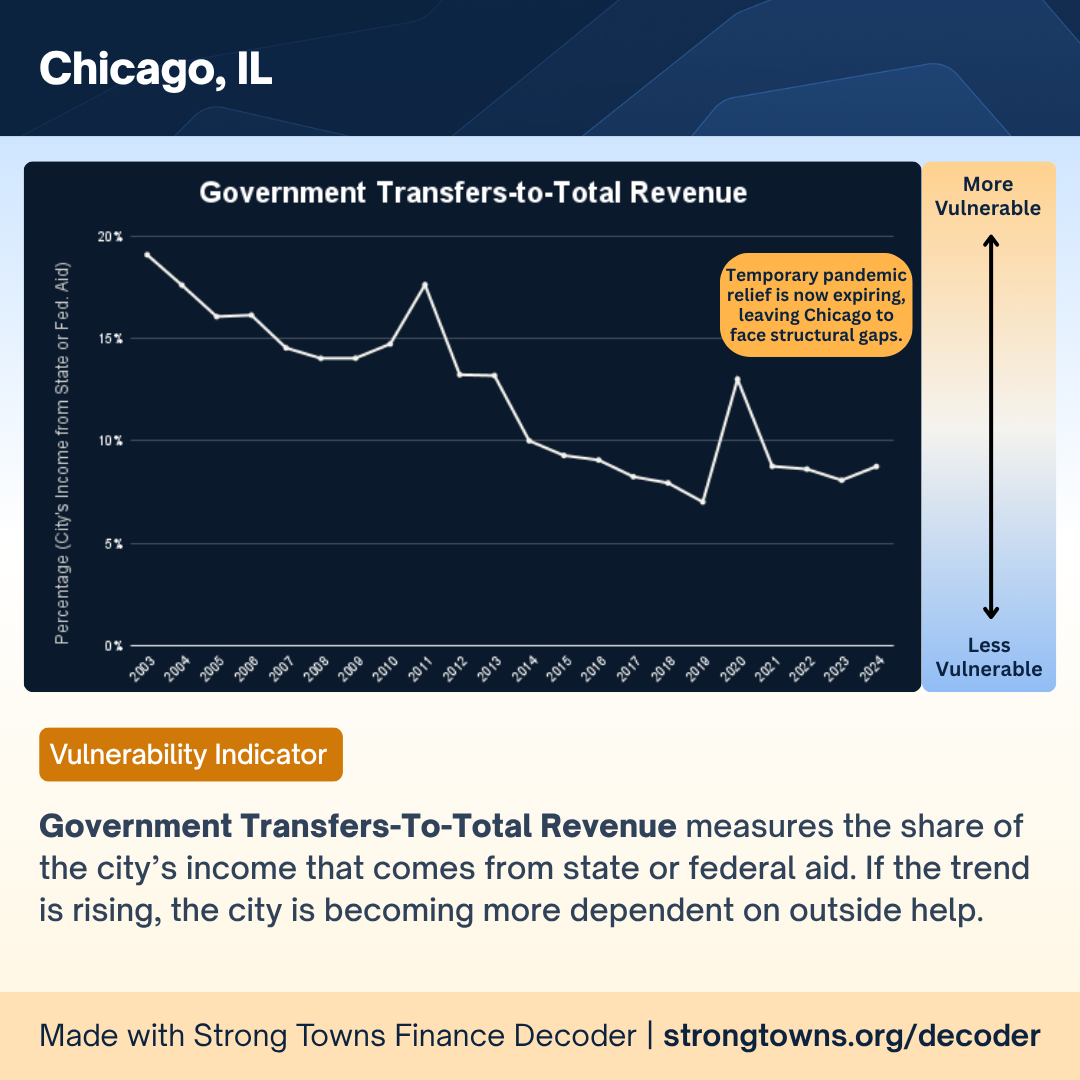

Vulnerability: “How dependent is the city of Chicago on external funding?”

Frustrated?

You should be.

Even if Chicago never technically defaults on its bonds, it can still “default” on residents: unreliable transit, unsafe gaps in bike infrastructure, crumbling roads, neglected parks, rising costs, public safety concerns, and reduced support for city workers and schools.

Contact your alderperson. Send them these results and ask them these questions.

Tell them that Strong Towns principles can break this downward spiral by prioritizing small, high-return improvements over risky big bets that have made our city financially fragile.

How did we get here?

Charles Marohn, the founder and president of Strong Towns national, argues cities run out of money for a simple reason: they built places that cost more to take care of than they ever earn back. After World War II, many cities spread out with wide roads, parking lots, and low-density development (known as “The Suburban Experiment”). This is cheap to build at first, but very expensive to maintain over time (streets, pipes, sewers, lighting, and services all need perpetual repair & funding).

At first, new development creates a quick boost of revenue, so everything appears to be working. When maintenance bills come due years later and the money isn’t there, cities often respond in two ways: they rely on more new development to get short-term cash or one-time fixes and band-aids—selling assets, borrowing, or making deals that plug today’s gap while creating bigger problems down the road.

This isn’t solely about bad management or waste—it’s about a broken system. Cities become financially strong by maintaining what they already have, growing gradually, and investing in things that pay for themselves over time, instead of relying on short-term fixes that trade long-term stability for quick cash.

Hungry for more?

Check out the data for yourself ➜ Google Sheet Link

And if you really want to get into the nitty gritty details ➜ Chicago’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports

And explore more insights from leading Chicago thinkers in this space at A City That Works and The Last Ward.